Eventually, the Triple Nickles would grow to more than thirteen hundred for

duty, six hundred in jump training at Fort Benning and nineteen hundred on the morning report rosters. But for

now the smaller number had some advantages. It had enabled them to concentrate on intensive individual and

small-unit training. Riflemen, machine gunners and mortar men had sharpened their aim to perfection. Training in

judo and other forms of hand-to-hand combat were intensified. They had time and opportunity to become superb

combat men. No goof-offs were allowed.

Moreover, men could be sent to schools for special training as riggers, jumpmasters, pathfinders, demolition

experts, and communications men. Jump demonstrations and small unit maneuvers had helped them to perfect the

tactics and logistics essential to many paratrooper combat missions, especially those requiring no more than a

company-size force, such as an attack on an enemy communications center, bridge, enemy headquarters or road

junction.

So when the order came to "skeletonize" to one reinforced company of eight officers and 160 men, the battalion

had a pool of the best from which to choose the super-best. It began with a downward shift of command, a move

for which everyone was fully prepared. The battalion executive officer, for example Captain Richard W. Williams

became the company commander. Williams, the eleventh officer to join the Triple Nickles, had come to the

organization as a first lieutenant from the 92nd Infantry Division. A well-built, muscular man, he was known as a

tough, aggressive officer, filled with imaginative ideas and a sense of adventure.

The battalion S3 (Plans and Training), lst Lt. Edwin Wills, the real "brains" of the training program, became the

company executive officer. The commanders of A, B, and C rifle companies became platoon leaders, with each

given his choice of an assistant platoon leader. Each former company commander chose his executive officer. First

sergeants became platoon sergeants and platoon sergeants became squad leaders.

This special company was ready to take on anybody. But suddenly midway through the rigorous combat training,

their destiny changed. By, April 1945, the German armies were collapsing. Americans were on the Elbe River - and

would stay there. From the east the Russians were moving on Berlin, and the fall of the German capital was only

weeks away. It seemed unlikely that any more paratroopers would be needed.

In late April 1945, the battalion received new orders - a "permanent change

of station" to Pendleton Air Base,

Pendleton, Oregon for duty with the

U.S. Ninth Service Command on a

'highly classified" mission in the U.S.

northwest. No one had any idea of what

the mission would be.

On 5 May 1945, the battalion left Camp

Mackall for Oregon. The move was

made in about six days. Ninety-eight

percent of it by rail the rest by battalion

motor vehicle or private auto -

including Graphite. Sergeant Lowry and

two other NCO’s brought the faithful old

Ford cross-country. (Graphite was a two-

door 1937 Ford, owned by Lt. Julius F.

Lane and Lt. Bradley Biggs). It was the

battalion’s service vehicle.

Apparently no one had noticed a brief

Associated Press item that had

appeared in the New York Times of 10

September 1944. With a Portland,

Oregon dateline headed "Fire Fighters

Use Parachutes", the story reported that:

"Crews have been dropped by parachute to fight forest fire in many areas of

the Northwest. A blistering summer sun indirectly caused fire in six areas in

Idaho in the last 48 hours. An eight man unit crew was dropped to fight a blaze

in the Lost Horse Pass Country of Idaho. Other parachutists were dropped into the back woods of Chelan National

Forest to battle 300 acre Fire".

On 6 May, while the battalion was still en route west, a woman named Elsie Mitchell and five children were on a

Fishing trip near Bly, Oregon. One of them found a strange object on the ground and the others went to investigate.

Suddenly the object exploded, killing all six. First news reports said it was a blast of "unannounced cause".

Actually, the object had been a Japanese bomb that had traveled across the Pacific on a hydrogen-filled balloon.

Though it remained a tightly-guarded secret for a time, the Mitchell's had been the victims of the first

intercontinental air attack on this country. Since early November, 1944 the Japanese had been launching these

"balloon bombs" - layered silk-like bags with clusters of incendiary bombs and explosives attached to them.

The secrecy continued even after one balloon caused a near calamity at the Hanford Engineering Works in

Washington state, then turning out uranium slugs for the atomic bomb that would destroy Nagasaki. One of the

balloons descending in the Hanford area became tangled in electrical transmission lines causing a temporary short

circuit in the power for the nuclear reactor cooling pumps. Backup safety devices restored power almost

immediately, but if the cooling system had been off a few minutes longer a reactor might have collapsed or

exploded and this country could have had a Chernobyl for which it was totally unprepared. The havoc would have

been unimaginable.

By January, 1945, however, both Time and Newsweek magazines had told of two woodchoppers near Kalispell,

Montana who had found a balloon with Japanese markings on it. By the time the battalion arrived in Oregon the

veil of secrecy was partially lifted. The War and Navy Departments had issued statements to the local populace

describing the bombs and -warning people not to tamper with anything resembling them.

The balloons, we learned, were made of silk paper and were thirty-five feet in diameter. Filled with hydrogen, they

would rise to a height of 25,000 to 35,000 feet. Then they would pick up prevailing air currents (latter called the "jet

stream") from west to east across the Pacific.

Each time a balloon descended below 25,000 feet from loss of gas and cooling, a pressure switch automatically

dropped a sandbag. This caused the balloon to rise again toward the 35,000 foot level. The balloons traveled up to

123 miles an hour, and took from 80 to 120 hours to reach the U.S., depending on weather. If the Japanese have it

figured right the last sandbag has been dropped only after the balloon has reached this country. At that time a

second automatic switch takes over.

When the balloon dropped to 27,000 feet a bomb was released. The balloon rose up and then down again and

another bomb is released and so on. When the last incendiary or bomb was dropped, a fuse ignited automatically

and set off a demolition charge which destroyed the balloon. Fortunately, all of the demolition charges didn't work

and some balloons we recovered intact. As part of this joint operation the U.S. Air Corps was increasing its air

patrols flown by P-51 aircraft to try to sight the balloons and shoot them down before they reached the coast.

Watchers along the coast also gave sighting warnings for air patrol action.

Not mentioned publicly at the time was the possibility that Japan might equip the balloons with the capability to

carry out some form of chemical-biological warfare. Their experiments with prisoners of war in the notorious unit

731 were not known until much later - but they began in 1937 and point to existence of a Japanese program to

develop for use deadly biological agents. Such agents quite possibly could have been delivered in quantity to the

United States mainland by balloons.

Also not mentioned was the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion. By now they knew that they had acquired a new,

temporary nickname, the "Smoke Jumpers", and that it would be part of the highly secret project known more

officially as "Operation Firefly".

It was clear that the white people of Umatilla County were not used to seeing many black faces in their midst.

Clearly there would be few of the joys of the service clubs and homes of Atlanta or Fayetteville. A few of the

troopers and a handful of officers would finally be able to find passable living quarters in town where their families

could join them. But these were few indeed.

When we arrived however, we had more pressing things than social life on our minds. We were assigned quarters

in the center of the post garrison area, close to the airfield and operations shed. Once settled, Captain Porter, our

commanding officer, and Lieutenant Wills, his S3, set out to get more details in our mission and operations plan.

The mission was soon clear enough. Working in teams out of Pendleton and Chico, California, we would be on

emergency call to rush to forest fires in any of several western states and join with the forest service men in

suppressing the blaze. At the same time, we would be prepared to move into areas where there were suspected

Japanese bombs, cordon off the area, locate the bombs, and dispose of them.

But this, we found, would call for an entirely new training program. We knew how to jump from airplanes. But the

heavily-forested areas of the northwest presented drop zones that were more difficult and more dangerous than

any we had faced before. We knew, how to handle parachute lines. But here we would be using a new type of chute

- one with special "shroud lines" for circling maneuvers. We knew how to read military maps, but the forestry

service maps were something new. We were used to explosives, but we had little, if any, experience in the

disarming of bombs - particularly any of Japanese origin.

Fire fighting was an entirely new experience.

All of this and our past "jumper" experience, was a prelude to the great experience of integration. Our mind sets,

individually and collective outlooks gave a new and different meaning to our lives.

Our new station, Pendleton Air Base, lay in Umatilla County, in northeastern Oregon. It was located on a plateau

overlooking the town of Pendleton. The base at one time had accommodated B-29 bomber air corps training units.

Now, with the war winding down, it had been skeletonized into "caretaker" status. The area was barren. We were

the only unit except for control tower personnel and a small engineer maintenance contingent. A consolidated

mess would feed the 555th officers and men together. It was, however, still commanded by a full colonel, a man

who would quickly make it clear that he disliked having an all-black unit at his station. He was careful that we did

not mix with his officers, that our area was inspected with undue meticulousness, and that the atmosphere of his

office was "cool" to us. We didn't give a damn about all of that because we enjoyed eating with our men and our

areas were always clean and well-policed. But we disliked the fact that we had to serve again under a prejudiced

post commander. We had just left one at Mackall. And before that at Benning. Such was the 555th’s lot.

The colonel's views were shared by the white civilian population in the area. In Pendleton, then a town of about

twelve thousand and famous as the home of the Pendleton Rodeo, the black soldiers, who were helping Oregon

save its forests, and possibly some of its people, found it difficult to buy a drink or a meal. Only two bars and one

restaurant would serve them anything.

Oregon had a long history of tensions over minority groups. First, in the nineteenth century, the Chinese had

suffered not only discrimination but outright violence. In the early twentieth century the Japanese had been the

targets. And in the 1920's, during a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, Oregon and Indiana were the two northern

state where the "invisible empire" seemed to find its most avid supporters. No doubt the Klan in Oregon had been

motivated by anti-Catholic, anti-"foreign" nativism than by a fear of blacks who were a small target indeed. The

1930 census showed the black population of Oregon to have been 0.2 percent. It had hardly changed by 1940.

Fire fighting, of course, was an entirely new experience. And it was in this field that a new training began on 22

May. Wills set up one of his brilliant training schedules. It was a three week program which included demolition

training, tree climbing and techniques for descent, if we landed in a tree, handling fire-fighting equipment, jumping

into pocket-sized drop zones studded with rocks and tree stumps, first aide training for injuries—particularly

broken bones. Troopers learned to do the opposite of many things they learned and used in normal--jumps like

deliberately landing in trees instead of avoiding them.

Troopers would jump with full gear, including fifty feet of nylon rope for use in lowering themselves when they

landed in a tree. Their steel helmets were replaced with football helmets with wire mesh face protectors. Covering

their jumpsuits and/or standard army fatigues, they wore the air corps fleece-lined flying jacket and trousers.

Gloves were standard equipment but not worn when jumping; bare hands manipulate shroud lines better.

Naturally their physical training program was intensified because missions often found troopers miles from

civilization and in heavily wooded and mountainous terrain. It paid off handsomely in that few injuries occurred

and only one death. On most of their missions troopers would work with forest rangers. The forest rangers could

walk up the hills like a cat on a snake walk. They taught the tough paratroopers how to climb, use an ax and what

vegetation to eat. At the time, troopers underwent an orientation program with forest service maps.

On 8 June, specially selected men began work with bomb disposal units of the Ninth Army Service Command,

learning the business of handling unexploded bombs.

Then came a new parachute. The parachute training was under a civilian, Frank Derry, who had designed the

special chute for jumping in heavily forested areas. A special feature of the "Derry chute" was its maneuverability.

By pulling the white shroud line the chutist could turn himself into a 360 degree circling movement. This, in turn,

gave him a wider choice of landing areas - a vital factor when trying to avoid tangles with the highest trees in the

thickly-timbered areas.

The parachute training included three jumps, two in clearings and one in the heavy forest. The C-47 pilots who

carried the 555th were a friendly, gung-ho lot, many of them were veterans recently back from flying "the hump" in

Southeast Asia. Their spirit and were a welcome relief from that which we encountered among most other whites in

the area. Whenever a trooper was injured, the pilots often beat us to the hospital to see how the injured smoke

jumper was doing. One group of smoke jumpers will never forget the pilot who brought them all home in one trip,

when a rule-book flier might have made at least two trips.

By mid-July, the entire battalion had qualified as "Smoke Jumpers"-- the Army's first and only airborne firefighters.

Soon their operations would range over at least seven western states, and in a few instances, southern Canada.

And there would be two home bases - one in Pendleton, Oregon and one in Northern California at the Chico Air

Base.

The main group would be based at Pendleton, with the mission of fighting

fires and handling bombs in Oregon, Washington, Montana, and Idaho.

Another group of six officers and ninety-four men would be based at

Chico, to provide coverage for California.

FIRST FIRE CALL

The first fire call came in mid-July 1945 to suppress a blaze in Klamath

National Forest in northern California. Between 14 and 18 July, the Chico

contingent supplied fifty-six men. It was a successful mission with no

injuries.

The first call for the Pendleton contingent come just a few days later on

20 July—to drop fifty-three men and two officers to fight a fire in the

Meadow Lake National Forest in Idaho. The group took off at dawn in

three planes, arrived over the drop zone (DZ) at 0830 hrs. Flying in trail

formation, each plane made a low level (200 feet) pass over the fire area,

looking for an acceptable DZ.

"After checking the wind by watching the smoke from the fire", Captain

Biggs recalls, "the pilot and I made the decision on a one thousand foot

drop—this was two hundred feet below the standard drop altitude.

Swinging around to take advantage of the wind, the pilot gave me the

green light and held the plane in a slow jump-attitude until I chose to

jump. Once out, I did not manipulate or "slip" my chute—I just floated

down like a wind dummy."

Meanwhile, the aircraft flew a 360-degree turn with the pilot and jumpmaster

keeping their eyes on Capt. Biggs descent trajectory to see if he had made a

timely exit; that is jumped at the correct landmark in order to land on the DZ

without steering the chute. When he landed in the center of the DX, the pilot

and the jumpmaster had their points of reference to follow. While they were

trained to handle themselves if they landed in trees, most of the members

chose clearings from force of habit and past experience.

During the initial pass of each C-47, an A5 container was dropped. The A5

contained axes, food, water, medical supplies and radio gear. This equipment

was sufficient to sustain the group until they linked up with the forestry department personnel.

From 14 July to 6 October, the Chico and Pendleton units participated in thirty-six fire missions with individual

jumps totalling twelve hundred. There were also casualties. In six months, more than thirty men suffered injuries

from cuts and bruises to broken limbs and crushed chests. One typical report listed under "injuries": "1 EM

(enlisted man) broken leg above knee, 1 EM knee out of place, 1 EM crushed chest."

On one jump in early August, one of the men suffered a spinal fracture. He remained on the scene throughout the

fire fighting operation. Then, realizing his men were tired and short of food and water, he refused to burden them

with the job of carrying him to the nearest airstrip. Somehow he managed to stand up and without help, walked

straight-backed for eighteen miles to the strip where his units would be picked up by C-47 for the return trip to

Pendleton. He spent weeks in the Walla Walla Hospital. Pure Guts!

Tragically, one man lost his life. The ill-fated trooper had landed in the top of a tall tree. In attempting to climb out

his harness and lower himself with a rope that each man carried, he apparently slipped or lost his grip and crashed

into a rock bed 150 feet below. It took three days for patrols to find his body.

Capt. Biggs recalls, "that all was not work. On 4 July we staged demonstration jumps for the local populace. We

saw the famous Pendleton Rodeo. Killer Kane and I learned to fly from two grand guys, Pat Stubbs and Farley

Stewart. We went to movies and took time to hunt and fish. I spent my spare bucks flying and seeing the west. We

had storytelling sessions nightly at the BOQ. And we found the black WAC Company at Walla Walla Air Base happy

to visit us (and our accommodations). Meanwhile, Graphite was serving as battalion taxi, cargo vehicle, and most

loaned-out vehicle for anyone needing a ride to town.

For the first time in the annals of military history of any nation, a military organization of paratroopers was selected

to become "Airborne Firefighters". The Triple Nickles became not only the first military fire fighting unit in the

world, but pioneered methods of combating forest fires that are still in use today.

The conduct of The Triple Nickles during the heretofore highly secret and untold story contributed immeasurably

to the well-being of most Japanese Americans in internment camps. If it were known that the Japanese balloons,

the first unmanned intercontinental ballistic missiles, had been successful in reaching our shores, the Japanese

military machine would have strengthened its efforts in that area. If the secrecy of the 555th’s operation had been

broken, there is no telling what additional maltreatment would have befallen the incarcerated Japanese in western

camps.

In October 1945, the battalion was assigned to the 27th Headquarters and Headquarters Special Troops, First Army,

Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In December, it was attached to the13th Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, where it

proceeded to discharge "high point" personnel.

In February 1946, after two months of no supervision and watching friends leave for home, the 555th was relieved

from attachment to the 13th Airborne Division and attached to the 82nd Airborne Division for administration,

training, and supply. It retained its own authority to discipline and manage its own personnel matters. Further

attachment was made to the 504th Airborne Infantry Regiment, then commanded by a colonel whose name will go

down in history as the originator of "search and destroy missions" in Vietnam. General William C. Westmoreland.

As an integral part of the 82nd Airborne, the finest American division of World War II and commanded then by

Major General James M. Gavin, a man who unlike so many white commanders, was color-blind, 555th went on to

become the first in many key areas of military innovations. Pioneering in integrating the Army was not the least

among them, an action that changed forever the character of the Army and the nation. Today it is an acceptable

fact that this pioneering by the 555th created the modern Army of today. And further, this achievement spread into

all sectors of society. For original Smoke Jumpers it is gratifying to know than many of the techniques and

equipment tested and developed during "Operation Firefly" are still in use in both civilian and military fire fighting

missions.

Traditional wisdom conveys to us that past events and history carry the portents and guidance for the future.

Dismissing that antiquated notion, these black soldiers relied on human perceptions of the known conduct of black

military men in the familiar hostile white environment both military and civilian. There was no necessity to try to

philosophize, theorize and intellectualize their role and contribution. Theirs was a new phenomenon to all walks of

American society and the meaning of the experience of pioneering in becoming the first military "Smoke Jumpers"

in the world. They shunted the windows of the past and dominated this scene by values of character, drive, pride

and unity.

By Bradley Biggs, Lt. Col. USA (Ret.)

Visit the National

Smokerjumper

Association Website

Click on the logo to the left.

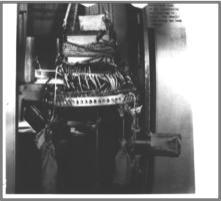

Pictured left is the

balloon portion and

below left is a side

view of the ballast-

dropping device on a

balloon bomb. The jet

stream carried the

bombs across the

Pacific to Northwest

forests during 1944

and 1945.

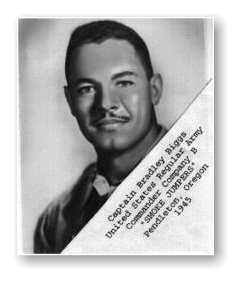

Captain Bradley Biggs

Bradley Biggs was the only

black officer to pioneer in

both armor and parachute

units. He made over 362

parachute jumps. After

retiring from the Army he made a

second career in academia in which he

held many positions, the last was

Associate Vice President for Business

& Finance of university-wide operations

at Florida International University in

Miami.

America’s First

All-Black

Paratroop Unit

The

Triple

Nickles

Bradley Biggs, Lt. Col USA (Ret.)

Foreworded by James M. Gavein,

Lt. Gen. USA (Ret.)

Let us travel back to the origins of this unit, its conversion from a highly trained and combat ready parachute unit to

the extremely dangerous role of "smoke jumping" and their performance in one of the best kept secret operations in

World War II.

Through December 1944 and January 1945, the Triple Nickles had continued to jump, maneuver, and grow to a strength

of over four hundred battle-ready officers and men. During that same period a far more deadly action was taking place

on the battlefields of Belgium - the Battle of the Bulge - the massive German counterattack in the Ardennes that began

on 16 December 1944. It lasted more than a month and before the Germans were turned around, the American army

had suffered some 77,000 casualties. Many of them had been paratroopers - men from General Jim Gavin's 82nd

Airborne Division and General Maxwell Taylor’s 101st who had made the heroic stand at Bastogne. The cry was out for

replacements, not only in paratroopers ranks but throughout the European Theater of Operation (ETO) combat

command.

At last we thought we were going to tangle with Hitler, whose embarrassment at

the 1936 Olympics of a Black American named Jesse Owens was fresh in our

minds. We eagerly anticipated pitting the Nazis against another group of black

champions - men like Walter Morris, "Tiger Ted" Lowry, Jab Allen, Edwin Wills,

Jim Bridges, Roger Walden, the list goes on." Biggs recalls in his book THE

TRIPLE NICKLES. He goes on to say that:

"We soon found that we would not go as a battalion but rather as a "reinforced

company". The reason was simple, we had not trained or maneuvered as a

battalion. The original orders authorizing the 555th said we would not begin

such training until we had reached a strength of twenty-nine officers and six

hundred enlisted men. This could have been achieved if commanders army-wide

had released volunteers and approved scores of requests for parachute duty."

Pictured Left is the

balloon portion and

below is a side view

of the ballast-

dropping device on

a balloon bomb.

The jet stream

carried the bombs

across the Pacific

to Northwest

forests during 1944

and 1945.

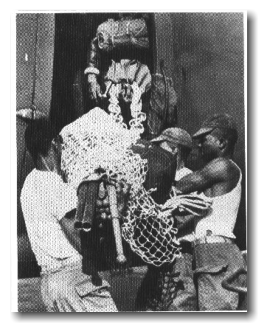

A group of "Triple

Nickle" loadmasters

heft fire gear into an

Army air Corps C-47

at the Pendleton, OR,

smokejumper base.