© Official Site Of 555th Parachute Infantry “Triple Nickle”. 2008

A Soldier's Story

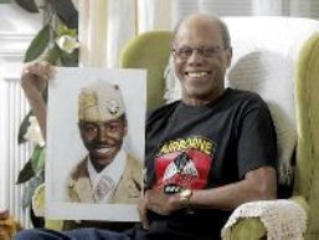

Willoughby served in historic unit

By By Laura McFarland

Nothing could have prepared Joseph Willoughby for that first jump.

In the moments leading up to parachuting from a C-82 at about 2,500 feet, Willoughby said the anticipation was

similar to what you feel on a roller coaster. He was excited. The order came, and he and the other men in the

airborne training class were out the door and plummeting toward the ground.

Then his parachute opened, and he experienced his first opening shock. It’s been 62 years since that day in July

1947, but Willoughby still remembers thinking to himself, “What the h--- am I doing up here?”

“The first jump is a trip. Everybody has a comment to make about their first jump. Some guys wet their pants. ...

My mouth was apart, and when I got that opening shock, my teeth came together so hard it made my gums

bleed,” said Willoughby of Rocky Mount.

Willoughby soon would love jumping and look forward to getting in an airplane every chance he could, but it

was determination that got him through those first few jumps. He had his eyes on the prize – being a member of

the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion.

At the time, the battalion, also known as the Triple Nickles, was the only option for a black paratrooper in the

Army, which did not desegregate until 1948, said Joe Murchison, president of the 555th Parachute Infantry

Association, Inc.

The battalion started as a company – 20 men chosen in December 1943 to test whether black men had the

courage and intelligence to be paratroopers, Murchison said. Seventeen of them made it through and became the

first members of the 555th Parachute Infantry Company. Several months later, the company was redesignated as

Company A of the newly formed battalion.

“Once the barriers were broken and negroes could volunteer for airborne duty, so many people volunteered and

were accepted for training and completed training. Since that was the only negro battalion, there was no place

else for them to go. So we wound up at one time having 1,800 men – three times the size we should have been,”

said Murchison of Tampa, Fla.

Though the unit was formed while World War II raged in Europe and the Pacific, the Nickles never were sent

overseas because of worries over mixing white and black paratroopers, Murchison said. In May 1945, the unit

was sent to Oregon to train to combat forest fires ignited by Japanese balloons carrying incendiary bombs. There

the paratroopers earned the nickname “Smoke Jumpers” as they fought forest fires of all kinds up and down the

West Coast.

---

Willoughby did not join the Army until January 1946 and was not assigned to the Nickles until around June

1947, so he never was involved in smoke jumping. After basic training in Louisiana, he was assigned to units at

Fort Benning, Ga., and then Fort Monroe, Va. For the 18-year-old Willoughby, who grew up in Manhattan, the

six months he spent at Fort Monroe were unacceptable.

“I didn’t expect to find what I found there. That company, which was all black and segregated, was duty

soldiers. They cleaned officers’ houses, mopped their floors, washed their windows, baby-sat their babies and

took their wives shopping. I didn’t join the Army to clean people’s floors and mop their kitchens and wash their

windows. I wanted to get out of there, and the quickest way for me to get out of there was to go airborne,”

Willoughby said.

In contrast, the 555th was all black from top to bottom and completely independent, Willoughby said. He was

assigned to the communications section of Headquarters Company.

Life as a black paratrooper still had its problems. Race relations were tense on base at Fort Bragg and in nearby

Fayetteville, and fights were a frequent part of Willoughby’s life. But among the soldiers in his battalion, he

made many lifelong friends.

“We were like brothers. We loved each other. We had to depend on each other. In the service, you depend upon

each other for your very life. When you go up in a plane and jump out of airplanes, the guy behind you has to

inspect your chute,” Willoughby said.

The Nickles stayed independent until December 1947, when Gen. James Gavin incorporated the men into the

82nd Airborne Division as the 3rd Battalion, 505th Airborne Infantry Regiment, Murchison said. The

integration of the 555th happened seven months before President Harry Truman ordered the armed forces to

desegregate.

Willoughby stayed in the army until 1949, when he returned to New York. He stayed there until he retired from

the New York Transit System in 1988, when he moved to North Carolina. He moved to Rocky Mount in 1998.

Though Katrina Rogers has known Willoughby for years, she had never heard of the Nickles until September

when she visited him and saw a picture of him at one of the association’s annual reunions. Since then, she said

she has been working trying to increase awareness of Willoughby and the Nickles to honor him and highlight a

mostly forgotten part of American history.

Rocky Mount Councilman Reuben Blackwell had a similar reaction when he met Willoughby at the Down East

Viking Football Classic, where the former soldier was honored for his service. Blackwell said he is looking into

what can be done to recognize Willoughby and the Triple Nickles.

“ That was an opportunity for me to learn something about American history and the involvement of African-

Americans in the war that I was completely ignorant to. Since then, ... I have a growing appreciation for the

contributions that they made,” Blackwell said.

Then and Now

“What the h**** am I doing up here?”

Willoughby thought to himself on his first

jump.